It can often feel like our job as parents is to motivate our children to do well at school and home. This can lead to a focus on rewards and punishments. However, research on motivation is very clear that the goal should be more about fostering self-motivation (or intrinsic motivation).

In this article, we explain the difference between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and offers some suggestions on how to effectively “motivate” your child.

Parents and teachers often feel that in order to help children do the things they want them to do – for example tidy up or get ready for school on time – they need to provide “motivation”. We often call this rewarding them for taking action!

Research has looked at two types of motivation that are important for parents and teachers to understand: intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. This relates to the reason why we do things – what drives the action!

[Types of Motivators] Courtesy of Janaki Kumar and Mario Herger. Copyright: CC-Att-ND (Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported)

Intrinsic motivation

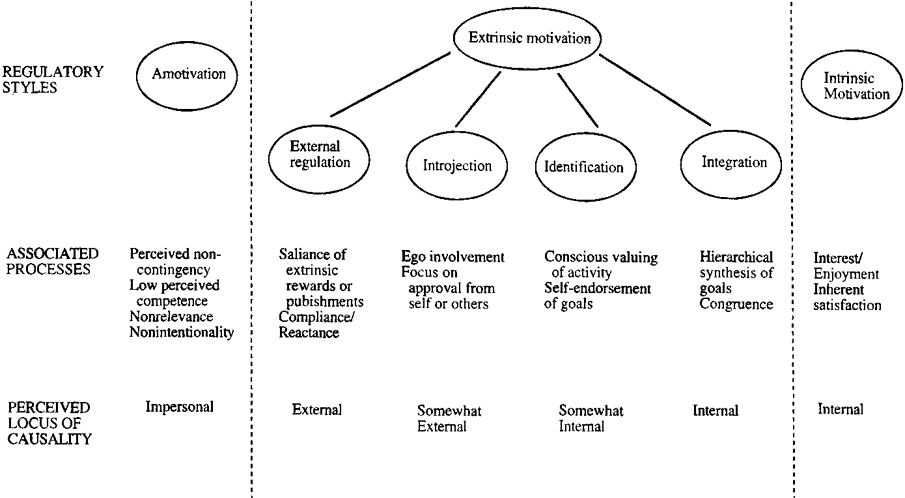

According to researchers, Ryan and Deci (2000), the reason or goal behind an intrinsically motivated action is about inherent enjoyment and pleasure. The motivation comes from with-in, drawing on the natural motivational tendencies of human nature and leading to high quality learning and creativity.

It can be facilitated by:

- Feelings of competence during the action (e.g. positive performance feedback)

- Sense of autonomy (choice and opportunity for self-direction)

Importantly, the activity must also hold intrinsic interest for the individual: novelty, challenge or aesthetic value.

What does this mean for parents and teachers: ensure the activities our children are engaged in are giving them this sense of satisfaction. If not, then how could we make it more fun and challenging for them? Ask them what activities they get pleasure from and why? The more we understand what drives this child from the “inside”, the more we can find ways to “self-motivate” them without threats and rewards.

It’s important to know, that this intrinsic motivation can be undermined by things perceived as controlling the behaviour; such as, rewards, threats, deadlines, directives, competition pressure.

What does this mean for parents and teachers: If a child is already motivated to perform a task, offering a reward or other form of “external motivation” may end up having the unintended consequence of actually making the child less motivated! If your child is interested and already enjoying doing something, allow them to be in control and avoid offering rewards. By letting the motivation for doing it remain “intrinsic”, the chances that they will succeed and become very competent at this activity are increased.

Extrinsic motivation

According to Ryan and Deci (2000) the reason or goal behind an extrinsically motivated action is outside the person and separate from the behaviour. Often this means motivated by a reward or avoiding a punishment.

Although often seen as a lesser form of motivation, it has been proposed that it exists on a spectrum and that certain practices can help increase engagement, persistence and positive self-perceptions.

- An important process in extrinsic motivation is internalization and integration – taking in a value and making it your own. This process is facilitated by relatedness – feeling connected, cared for and respected by the person who is asking you to perform the task. Motivation comes from the fact that the behaviour has value to a significant other.

- Autonomy is also important for extrinsic motivation. For example, a student can do work to please parents or avoid punishments – in which case she would feel she had no choice. However, imagine if she was doing the work because she wanted to get better at a sport or activity she loved. In this case because autonomy (choice) is involved, the psychological and learning outcomes will be improved.

- Competence is important and the feeling that you can do it is important for internalising the goal.

FIG. 1. A taxonomy of human motivation from Ryan and Deci (2000).

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary educational psychology, 25(1), 54-67

Intrinsic vs Extrinsic: Take home message

- Encourage self-motivation: learn what “intrinsically” motivates your child and allow them to be in full control of these activities e.g. their favourite sport, music, art, academics pursuits. If you are unsure what these activities are, ask them to tell you about what they “love doing’!

- If you feel your child is not intrinsically (self-motivated) to do something that you really need them to do (such as chores, school-work, behaving appropriately) you may decide to use extrinsic motivation (rewards or punishment). In this case, increase compliance by using relatedness, autonomy and competence. This means building rapport with the child and explaining why this is important to you, find a way to give the child a sense of control over the activity, and ensuring the task is something they will be able to do and will get a sense of achievement from! In fact, applying these three strategies (relatedness, autonomy and competence) when asking your child to do something might even mean you can skip the reward and punishment altogether!

Parent Helpline

If you would like to talk more about how to motivate your child, our telephone support workers are happy to talk it through with you. Call our free nationwide Parent Helpline on 0800 568 856.

Related links